Money and my high-minded views as to the arts

Having spent a large part of my life in the financial world, starting first out with a little laissez-faire working as an introducing broker to Swiss banks, after my stint with insurance and assurance. Later on forming the first financial and estate planning consultancy for high net worth individuals in the U.K. (Associated Financial Planning, AFP). Initially, working with equities (stocks and shares) and sovereign debt (government bonds) the essential part of any investment portfolio; however, I slowly become quite an expert in so-called alternative investment, commodities, specific the precious metal. What is more, I knew whom to contact for first-class expertise.

As to the visual arts, I never considered them from an investment point of view. When I at one stage owned and operated the largest Scandinavian bullion dealer and International Resources, a commodity dealer, trading in the soft commodities like soya bean, sugar, coffee, cacao, but also the hard commodities, the metals – I become an advocate of alternative investment.

Art and Money

There is something dysfunctional about how artist receives recognition and succeed. Also, how we value art, the art market is simply not transparent and, in many ways, operate as a black box. Like gold and most precious metal, art is a purely speculative investment. Its price is driven more by fashion than financial calculation, and it constitutes a more sanctified object of capital accumulation than gold in that the art market marries high aesthetic values to base financial instinct. Yet, for some, it should never be a financial asset at all.

Art is an experience, something that enters your mind, your life and experiences, and to be essential to our being. Art is for making us think, possible enjoy, heal, casting spells, for crying, provoke your thoughts, make you happy, fall in love, and even give you some new perspective and creates thoughts. To me, art is a fundamental part of being and of living. I could not imagine a world without art. I agree somewhat with Fyodor Dostoyevsky’ statement “Beauty will save the world”.

Money has corrupted the arts and made everything somewhat totally absurd—a little like the Tulip bulb speculation in Holland, which became so widespread by 1636. I very early had an entrance to the art by my Norweigian business partner Edgard (Midling Jensen); he had studied opera singing in Rome and later had a company in Denmark, dealing in lithographs and limited editions providing me contact with many artists at the time. However, it was first when I went, with a friend, to David Hockney’s studio in Holland Park, in the early 1960s, that I really understood the personal aspect of the art and the artist. He said, “I will be the greatest British artist one day” and indeed he became, not that I think he is, never minds, he became. It was all about marketing and selling an artist and his work.

The art market has been for the financial service industry a place to laundering money, receives fiscal benefits and promotion. It was regularly used by American taxpayers to donate art to charities, with considerable tax benefits; this has contributed to much speculation and at times dominated the so-called “value” of art.

I agree with the British economist Keynes; Keynes had serious reservations about speculation in works of art. Yet this idealistic position sits very oddly with the historical reality. Artists, composers and literary people have always dirtied their hands and often made a great deal of money. Latterly, some have even boasted about their commercial motivation.

I have seen big changes taking place in the visual arts during my lifetime, starting with the C.I.A. backing the 1950s American art scene, including the Abstract Expressionist, selling the U.S.A. and American values, engaging Madison Avenue’s best media promotion. This, together with the ingenuity and cleverness of the British auction houses, has no doubt created a different environment to sell the arts. The latest development in the last 40 years, lawyers and bankers have been progressively involved and made sure to milk the cash cow by their power of managing provenance and estates.

Andy Warhol estate is a typical example of this gravy train and the huge surge in large private collections. I did agree when the French introduced that artists should be receiving a percentage when their works are resold; this to some extent, stops artists from being exploited by dealers.

Modern technology has allowed the development of many new art forms and the means to promote and sell art. In the last 20 years, I have observed the “hard sell of contemporary art” surprising also by the British with their Brit Pop. By creating this wider market to sell art to and indeed the concept of sophistication, bringing people to major art shows have paved the way to sell a lot of art to Asia and the developing nations making it a bonanza for the auctions houses.

I recall back in the 1960s and 70s that contemporary” Modern Art” seemed detached from everything else and nobody talked about it except among a small group of people. Even in the 1980s in the U.K., it was hard going selling contemporary art, and I found, even selling to the well-off community of Mayfair, it was difficult. Most of the people came to the openings to enjoy the Champagne and canapé, not to look at the works.

The relationship between the pop world and the art world had a little spurting in the late 1960s; however, it really took off in the 80s and 90s. I believe television played in the U.K. an important role. I have always wondered how fortunate the British are with their language, both as to the arts, but also in business.

When I worked with the English Speaking Union, in Mayfair, I had difficulty getting across, that they should not alone look to promote English in nations that already speak English, but the fall of the Berlin Wall had opened up overnight a market for millions of East-European and former Soviet citizen to learn English.

As a Dane, I have observed the benefit of the English language, the incredible soft power of the Anglo-Saxon language, providing the world market in pop and communication. The interesting thing, the British take it for granted, and only a few understand the great value of English. Everything has to be sold, and the form of communication is vital.

It is interesting that contemporary British and American artists are generally more known around the world, all due to English. We need more to bring artists from Asia, Africa, and South America, into art history but also today’s world.

Money in the Arts

As to money and artist, going back in history, artists have always tried to escape from dependence on patronage and the advantage of financial security. In recent centuries, painters like Joshua Reynolds made serious money from his profession. Reynolds had been observing the business model and financial success of such continental artists as Rubens.

In Renaissance Europe, the arrival of the printing press provided the artist with the opportunity to mass-produce copies of their work and to develop a broad European art market. Initially, the artist, as a marketing tool for promoting their painted work, used prints. In the late fifteenth Century, Albrecht Durer devoted himself increasingly to selling copies of the woodcuts and engravings printed in the Nuremberg workshop. It was far more lucrative than painting, and Durer was an astute businessman, as we today have seen with Hirst and Koons.

Some years ago, the New York Times observed, no artist has managed the escalation of prices for his own work as brilliantly as Mr Hirst. An equivalent allegation in the U.S. securities markets would have more serious consequences.

An art market is indeed a murky place, and I do not believe that Robert Hughes has been exaggerating when he said that the art world was “the biggest unregulated market outside illicit drugs”. That said, the main buyers of art are big enough to look after themselves.

A global industry, including the leading auction houses Christie’s and Sotheby’s, is devoted to authenticating and selling works of art, but no one can honestly be sure of the status of an old master. Debate still rumbles over whether “Salvator Mundi”, which sold for $450m in 2017, is wholly the work of Leonardo da Vinci. The idea of the individual old master emerged in the 18th century, at the same time as auction houses.

The inconvenient truth is that there is no clear answer as to whether or not a work is by Leonardo, even if fortunes rest on there being one. Not only is it an opinion, but the question itself may not even make sense.

I recall reading about William Blake saying, that where any view of money exists, art cannot be carried on. William Blake’s wisdom, which was rooted in a fundamental truth: we can no more measure the value of a Shakespeare play than reckon the utility of Beethoven’s late quartets.

Much in the arts is inherently unquantifiable in financial terms and where it is quantifiable, the quantity may say about the well-being or aesthetic delight that the art in question imparts.

I have been observing the contemporary art market for the last 60 years and have constantly been surprised by the huge capital appreciation of the business, the volume of art moved by the auction houses. As I have been most critical, believing that reality ultimate comes to us all and the market will correct itself one day. Nevertheless, the prices have just gone up and up, and it looks the party will go on.

A curator who travelled extensively in Asia, told me more than 15 years ago, that alone China, required more than 2500 contemporary art museums, which is a lot of art. Having been a patron of The Royal Academy of Art, I have always said that art has to be sold, repeatedly, everything has to be marketed. Even a dentist and lawyer has to be able to promote his services. I used to tell art graduates that the most talented artist might never be known, as they were not promoted.

Today with the Internet, it has become an even playing field for many artists, but it is a worldwide media show, where only the ruthless will succeed, with fashion coming and going.

Art auctions are, incidentally, notoriously susceptible to manipulation, and dealers’ ethics often leave much to be desired.

The late Australian art critic Robert Hughes understood visual art and could see the merry-go-happy business. Considering that not only the art market but most governments pursue the same path, creating wealth and money, working the money printing presses at full capacity, letting future generations pay their debts, or ultimately go bankrupt, who am I to say anything? It is all a merry-go-around. Notoriously susceptible to manipulation, and dealers’ ethics often leave much to be desired.

The U.S.A. keeps printing trillions of paper money and debt calling it Q.E. (quantities easing), the debt of the U.K. soon will exceed £ 2 trillion. The Chinese have learned to do the same, just keep “creating money” and leave the bill to the future; one thing is for sure; the bill has to be paid one day.

As a Dane, with Hans Christian Andersen, the little boy, who had not been told, will shout out the emperor, have no clothes on. However, who am I to judge, also I believe as Ayn Rand that art is a recreation of reality according to an artist’s metaphysical value judgments.

To me Joseph Beuys had not been shot down, as a Luftwaffe pilot in 1943, in Crimea, we would have been spared a lot, including all the performance art, installation all favoured by so many museums curators today. The Dada and Marcel Duchamp showed the way already in 1928, as to the visual arts; however, to me, it becomes dark, grey and ugly with Joseph Beuys.

Reading recently about Impressionism again, I see so many important painters who were born in 1841, a hundred years before me, including, Frederic Bazille, Marie Bracquemond, Armund Guillaumin, Berthe Morisot and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. I agreed with Renoir when he said, “for me, a picture must always be something lovable, pleasurable and pretty, yes, something pretty. There are enough unpleasant things in this world: we do not have to produce any more” To me, Jeffrey Koons, Andy Warhol, and Damian Hirst are more about entertainment and pop culture than beauty. Jeff Koons Rabbit fetched Euro 81.4 million, a record for the biggest sale of a living artist. I have met Jeff, and I know he will again be laughing all the way to the bank.

I did accept some of this “art” going into some of our many exhibitions under The Art for Mayfair, but only because it came from top graduates from Goldsmiths and Central School of St. Martins. Although I accept his importance and that he helped to foster the Young British Artists, born in the same year as me, Martin Craig-Martin is also a conceptual artist producing entertainment, as far as I am concerned.

My life with visual art

From early childhood, I wanted to become an architect, possibly because when I was 4-5 years old, my mother used to help out at an architect’s office in Copenhagen. I believe this brought me very early in close contact with sunny white rooms, colours, pencils, large desks, large free-standing plants, and most of all, the Danish concept of modern “hygge”, and I felt comfortable with contemporary art and environment. I also believed very early on the importance of architecture, as it is the largest, man-made, object around us. Jean Nouvel, the great French architect, said recently, “Architecture is an art – that’s what people forget more and more. It has the potential to affect us, to move us – that’s the aim of all art.” Thinking about all the many museums and concert halls he has created – “it’s really the mother of the arts, it can nurture the others”. I believe this is the case, and it nurtures our view of the arts. I also believe that Bauhaus had a great influence on Scandinavian architecture and art.

The studio where my mother worked turned out that the architect’s office was a partnership working with Arne Jacobsen, one of the greatest Danish architects.

My early involvement in the arts came to school. I went to school in Copenhagen, next to the Carlsberg brewery. The best teacher we had was the art teacher; he was a great inspiration to us and the only true teacher, I respected at the time. I did not, however, continue in the arts.

Because, I had relatively good handwriting as 12/13 years old, this lead me to do calligraphy and make various cards and appointments in Italic with a goose feather pen, providing me with additional income. In fact, I even started making scrolls with official appointments to hang framed on the wall.

As to drawing, I entered a competition, a poster completion, when I was 14 for Carlsberg Brewery. This was a poster for their horse-drawn vans, where they had a large space for advertising. The poster I made stated, “Hvorhen jeg i værden rejser vil jeg altid møde ølets kejser – H.O.F.” (where ever in the world you travel you will meet the emperor of beers – Hof, the Danish text was far better, as their most important beer at the time was called Hof (Royal court). I still recall, the payment which was D.kr. 1500, much more than my stepfather made monthly working at Carl Alders. My poster had the Eiffel Tower, Empire State Building, Big Ben, St. Peter’s Church in Rome, and other famous landmarks around the world, all drawn into one city space. I took the inspiration from the great poster artist, Otto Nielsen, who made many of Scandinavian Airline System’s posters.

I did not continue in the arts, partly due to the fact, that I very early worked during the day and went to a private school at night with much older people, many were graduated as engineers and architects, having gone through polytechnics education and needed academic exams in order to go to university.

During those years, I had up to 3 jobs a day, working for a book store, greengrocer, and in the morning at Copenhagen meat town (Kødbyen). At the book shop, I used to decorate the windows and made attractive displays with books. Since I had already much earlier worked for a greengrocer, I had learned to polish fruits and stag them in attractive ways. I wrote the prices displays for vegetables and fruits, later for the book shop the displays and comments about the books.

When I was 15, I worked for a retired Danish investment banker, Eiler Baastrup, in the afternoon for some hours. My work was mainly to sit and listen to his life stories. He was a very famous banker, and as he was in his 70s, he had a lot to tell about his past and Danish history. He had been married to the National Bank’s director daughter and was a very controversial banker with economic theories and responsible to the money exchange after the Second World War.

Eiler Baastrup somewhat encouraged me to early entry into the business, at a very early age, in fact, at 16, where my mother had to sign for me, as in Denmark one could not even have a bank account before the age of 21. Since we extensively used the Bill of Exchange for finance, I still recall her concern about the large amounts; she was even concerned about the amount of money we made.

So, at 16 years old, I went into a business partnership with a Norwegian, in a shipping and ship-provision auditing venture. I designed the logo for the company (International Consultant for Merchant Marine, ICMM) with the earth globe (with the ocean in light blue) and the first nuclear merchant navy ship Savannah sailing out.

My Norwegian partner Edgard Midling had various business interests including acting as an art dealer specialising in Danish contemporary lithographic and prints. This allowed us to see many artists and learn about the famous Copra group with Asger Jorn.

Edgard Midling was educated as an opera singer in Rome, after the war, where he had been a freedom fighter, a very famous one in Norway. Due to his singing, I become very familiar with Opera, as we travelled a lot around in Norway in his car and attended many parties with Norwegian artists. Sadly, our company only had a short life, because we only could exploit a patent for 18 months, during which time we made a lot of money.

Due to the amount of money we made, he left for Norway, and I become responsible for his tax, resulting in that I very early become a tax exile ending up living in Portofino, later travelling around the Mediterranean, using bulk carries under the flag of Norwegian shipping companies, I had previously got to know through our sale of milk machines. At the time these relatively small bulk carriers took some passengers.

It was my intention first to study in the U.S.A., where I had some family; however, I changed my mind, at least for some time, as I got in contact with a stockbroker in Caracas, who advertise in the International Herald Tribune for an assistant. So I went across the Atlantic, seasick all the way, practically lock-into my cabin, as I was so sick losing ten kilos. I still recall the kind Swedish chamber lady who took care of me; it was one nightmare. What happened hereafter, have nothing to do with the arts, and I have written about all this in another place.

I was not able to go to the U.S.A., and I did not stay for more than a few weeks in Venezuela, but I did have some great experiences going to Brazil and later Cuba. In Brazil my connections, allowed me to have a written introduction to Oscar Niemeyer’s’ office in Rio, when I was 18 years old visiting Brazil, I even went to see Brasilia in the very early stages, and met Louis Costa, Niemeyer’s partner, although I never met Oscar Niemeyer. After visiting this great architecture, I wanted for a time to be an architect. This stayed with me for some years, even after I married, however, I never got around to taking the big step.

In late 1961 and 1962, I managed a little retail shop (pipes, cigars, and tobacco) in the Royal Hotel in Copenhagen, built by Arne Jacobsen, who had designed everything including the shops and interior, every single item. Considering, Arne Jacobsen smoked a pipe and used good tobacco, he came by the shop, where I always took the opportunity to speak to him about the “free South American, Le Corbusier architecture” versus the Scandinavian. Where rightly, in my opinion, people like Oscar Niemeyer considered houses as big outside sculptures, where the majority of Scandinavian architects would start with the inside of a building and focus on the interior.

My wife and I moved to Stockholm in late 1962, where I attended several events at the Moderna Museum, including with many American pop artists, seeing Jasper Johns and several happenings (my first), Claes Oldenburg, William de Kooning and Roy Liechtenstein.

Later working for a Swiss private bank in Geneva, I attended one meeting with Le Corbusier with a director of the bank back in 1964, Le Corbusier had been a big inspiration for Oscar Niemeyer and many contemporary architects. Le Corbusier also painted and designed furniture. Interestingly he is buried close to me, next to Cap Martin, at Rochebrune in the South of France, part of the same mountain Mont Agel where our home Villa les Anges is.

When working introducing clients to Swiss banks and more, I made it even a speciality to work with architects and consulting engineers as clients in the U.K., like James Sterling (the Economist building), Richard Seifert (employing 900 draughtsmen, built the ugly barracks at Hyde Park and Centre Point), Sidney Kaye (built London Hilton Park Lane) Guy Morgan (built Bowater House, now One Hyde Park, still standing the Royal Thames Yacht Club. Guy Morgan was a protege of Edwin Lutyens and made a lot of money during the war building airfields, both my wife and I enjoyed his many dinner parties in Eaton Place., where we met a lot of famous people.

I also got to know very well John de Breamaker, and Ove Arup (a Dane) and his partner Philip Dowson. Ove Arup created one of the largest partnerships in the world. An independent firm of designers, planners, engineers, consultants, and technical specialists.

As a child, I had stayed in a summerhouse close to Jøn Utzon for one summer, and I had seen him. Ove Arup later told me of the great difficulties with building Sidney Opera House, because Jøn Utzon’s plans could not be built for years without the advancement in computer technology. Utzon was an unknown Dane when he in January 1957, was announced as the winner of the “International competition for a national opera house at Bennelong Point in, moreover, that Over Arup never are given the credit that he deserves as to this building.

In 1974 I established Scandinavian Mint and later planned together with Reader Digest to make small sculptures (Marquisette) by famous artists such as Rodin, in limited editions for gold card members of Dinners Club, Readers Digest, and American Express during the 1970s. These small sculptures were meant to be paperweights, although, they all were in solid platinum, gold, and silver.

We made the Fairy Tales Spoons using Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tales, inspired by the 11th-century apostle’s spoons. I designed the whole concept and also the display cabinets for the spoons to hang in. I was very critical of the engravings and even went to Austria to try to find craftsmen.

AXIOM GALLERY

In 1964 I got to know an architect James Crabtree, who had a small architect office in London. He was an avid art collector of old master drawings but wanted to open a gallery in Duke Street Mayfair off Grosvenor Square, showing contemporary art. I helped him to raise some of the money for the gallery and in return, had a share of the business. Because James Crabtree worked as an architect and first and foremost collected old master drawings, I do not think Axiom Gallery received all his attention.

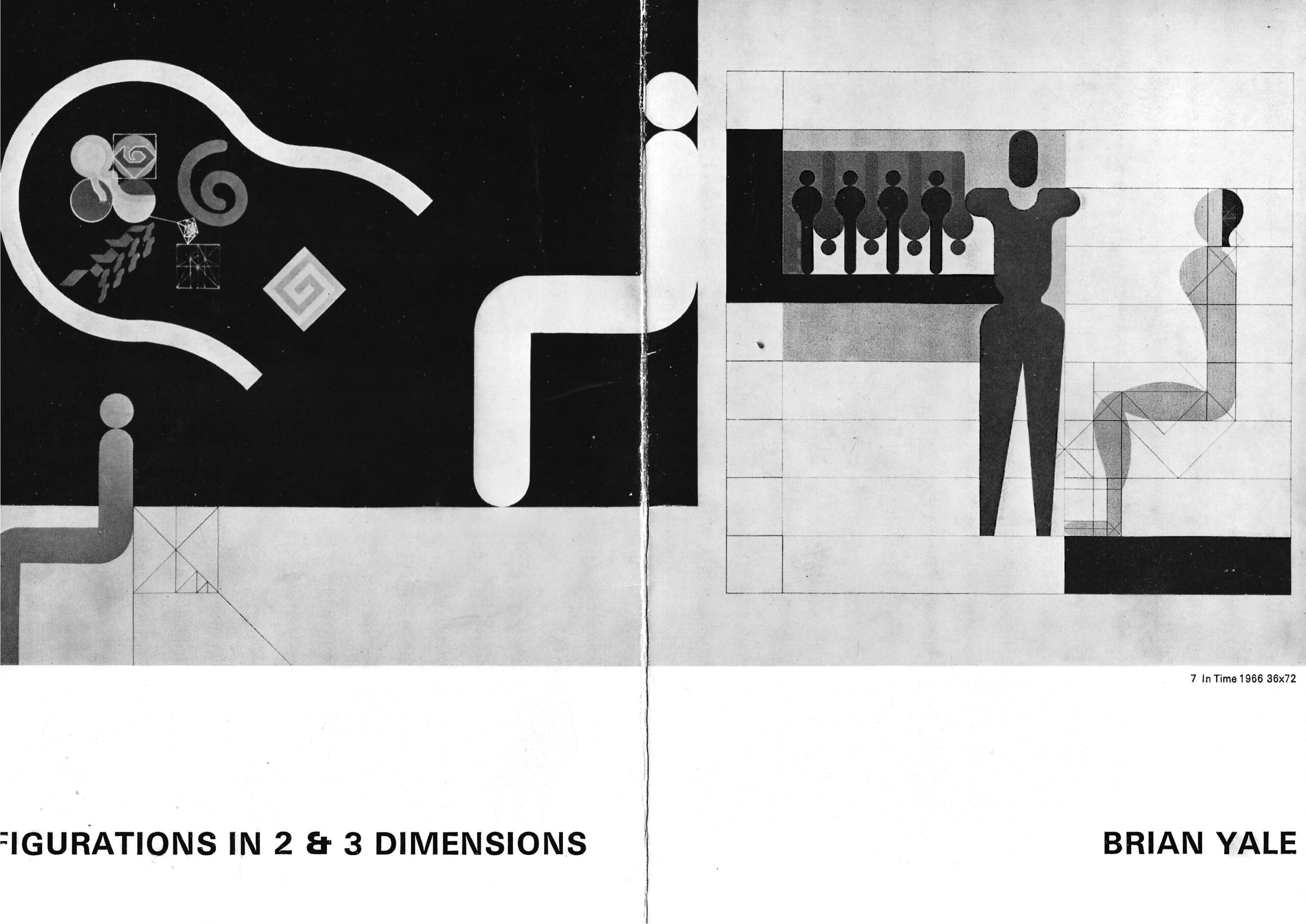

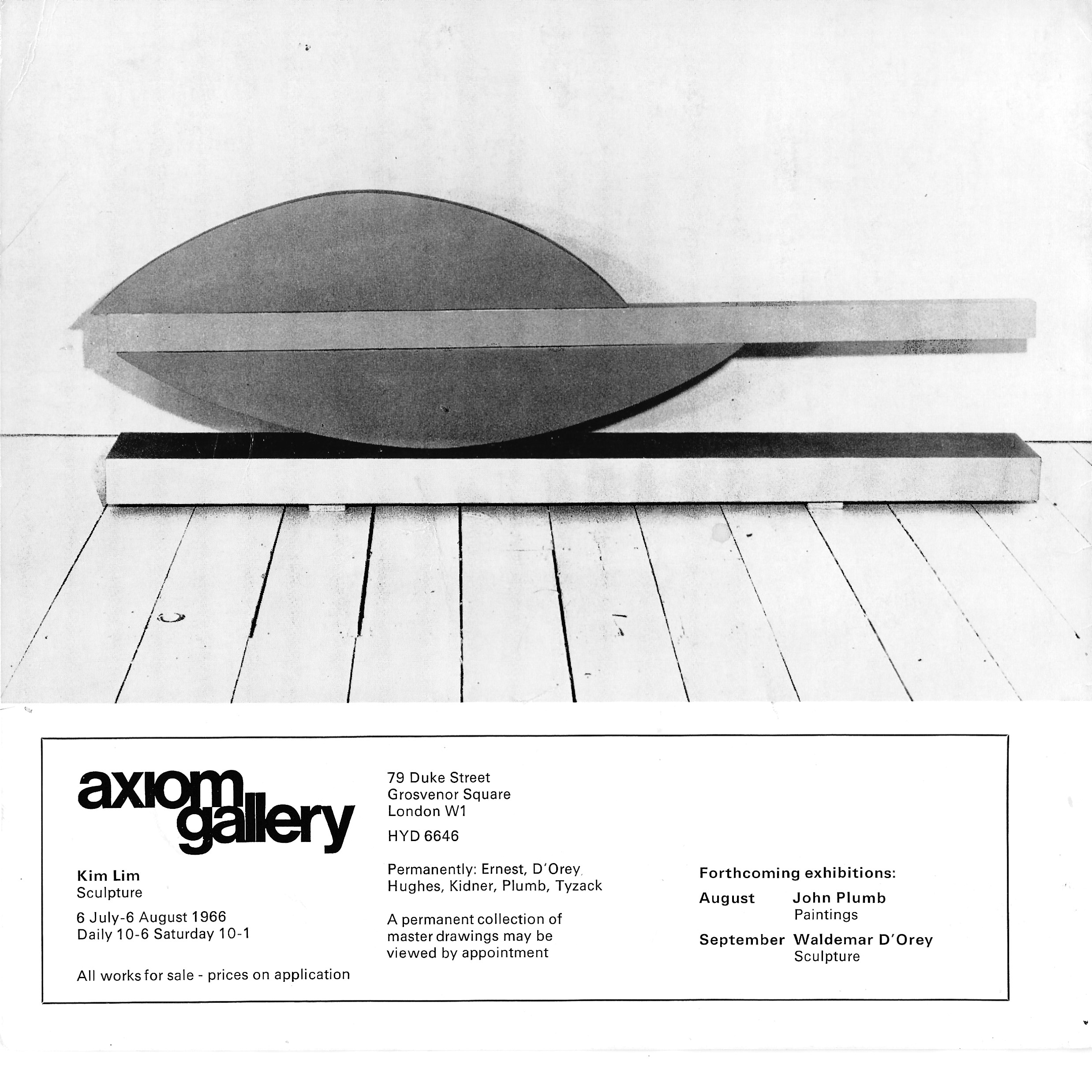

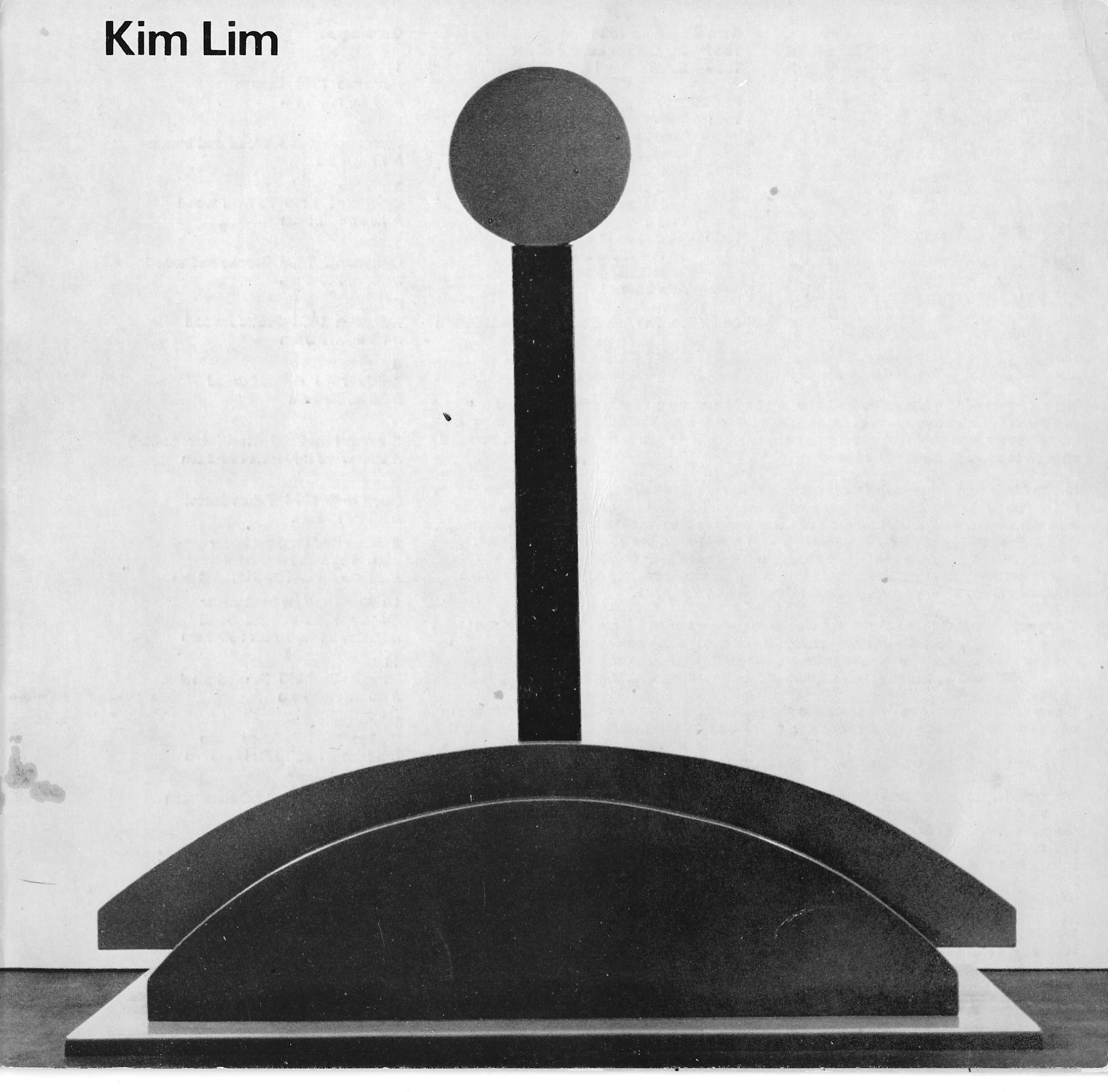

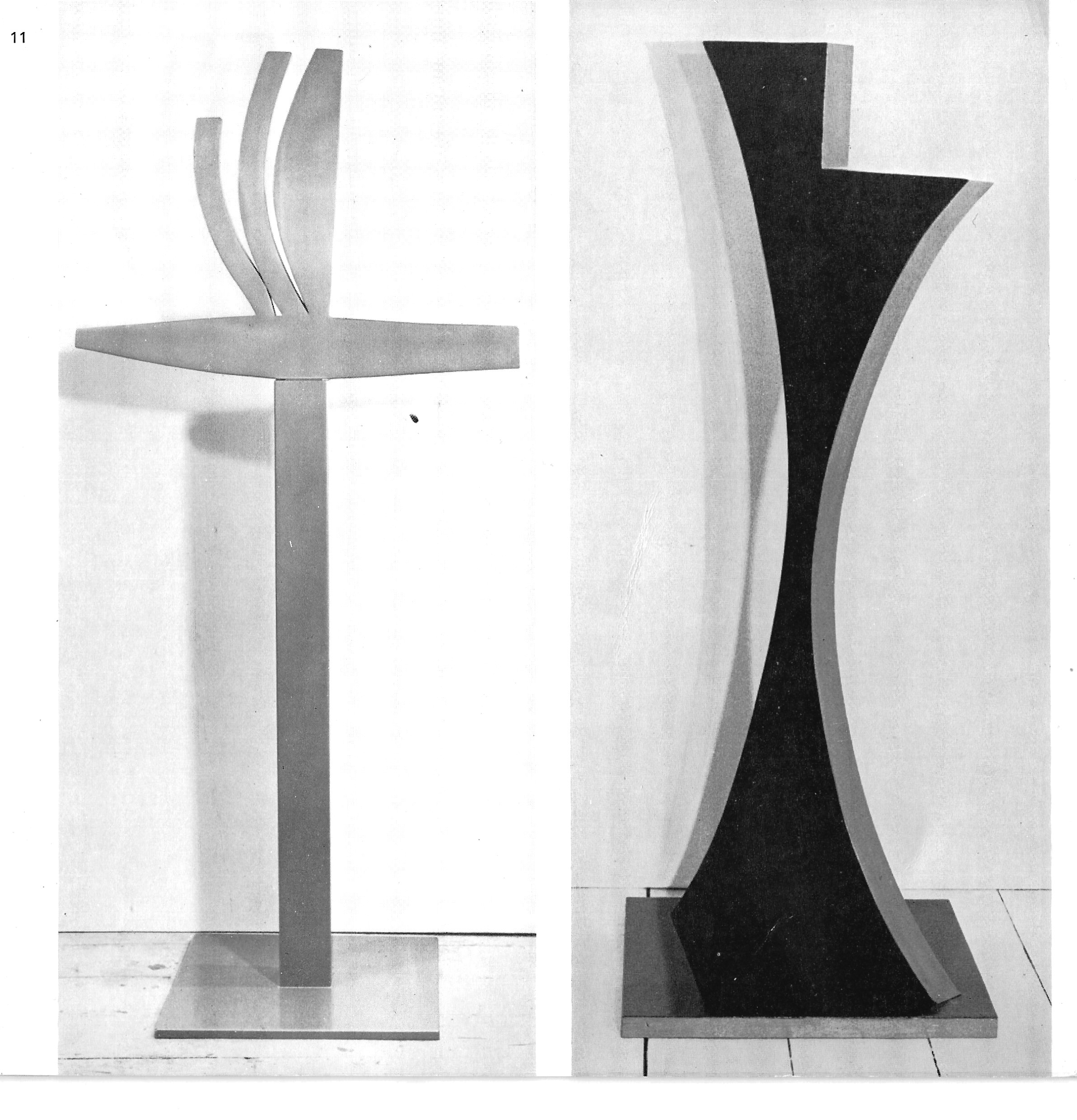

Axiom Gallery opened in May 1966 at 79 Duke Street Mayfair, specialising in Constructive art. The gallery becomes, from its start, a leading centre for constructive art.

Hans Haenlein MBE designed the gallery in 1965; interestingly, he, later on, involved himself with the local community, as I did and became president for The Hammersmith Society, an amenity group. I was chairman of The Mayfair Society.

Haenlein designed a space that became one of the first retail premises to take advantage of the former Victorian coal cellars, by opening up the pavement, so light could come down, providing an ideal gallery space in the basement.

The Axiom gallery had many famous artist exhibitions, including Richard Paul Lohse in 1968. We also found many artists which later became famous, like Kim Lim, we held two solo exhibitions for her work in 1966 and 1968, her work was later acquired for museum collections across the globe,(see: http://Kim Lim (hepworthwakefield.org)

Our gallery manager Nigel Greenwood, started in life after the Courtauld, serving an apprenticeship as the gallery manager. He went on to be one of the highly respected art dealers and the only dealer to be asked by the Hayward Gallery to mount an exhibition and to select the Hayward Annual exhibition. Nicholas Serota wrote his obituary in the Guardian.

The gallery specialised in constructive art, something, I did have some knowledge about, due to my interest in architecture. I followed both Russia and the Dutch origins, just after the turn of the Century. Constructivism had always been one of my interests. The gallery becomes the most important gallery for Constructive art at the time in London.

We lived just around the corner, so to say, and I started spending time in the gallery. My wife, unfortunately, did not like my involvement with the arts and the “funny people”. She did not even attend the openings where many important people came. James had been married many times, and that also kept her away from getting along with him. This all caused a rather negative situation and sadly reflected my involvement with the gallery. After the gallery closed, I kept the name of the axiom gallery.

On many Saturdays, James and I used to go to the East End and out of places in London, where he would buy master drawings from 17th, 18th, and 19th-century art, many students’ drawings. In fact, I recall he once purchased near a ton in weight, which we loaded onto a lorry. Among these drawings, he found jewels to add to his large collection, which ultimately started ending up at auctions.

Since James liked the female company, like me, we often went afterwards to Kings Road watching all the hot pants, walking along the pavements, sometimes seeing a car crashing into a pole. Again all this did not go down with my wife, something I understood later. However, at the time, this was Swinging London, and I was a young man. Nevertheless, I spent lots of time with my boys, which none of my male friends did with their families.

An interesting, after note, when I returned to Mayfair in 1986, I found that the gallery space, in 79 Duke Street was now H. R. Higgins, specialist coffee and tea merchant, with a Royal Warrant. Since I believed in coffee would be far more successful in the future with many coffee houses, I made an offer to buy the business. Unfortunately, the owner did not wish to sell as his son, the grandson of the founder wanted to carry on. I was right about coffee shops and the success of coffee. Mr Higgins told me that the Queen always travels with tap water from London, as she like the water used when making her coffee.

C.I.A. Funding

Considering, that in the mid-19605 considerable funding could be taken from the American Embassy, when showing American artists, we had some important openings, with large attractive catalogues and big openings and events, even showing at the American Embassy’s theatre, with big receptions. I recall two such openings attended by an art collector Paul Getty, who was drinking milk, instead of Champagne and appeared very tiny.

People from the U.S. Embassy actively promoted American contemporary artists but wanted English galleries to take part.

It was first ten years later that I received confirmation about the C.I.A.’s involvement in the arts. This was confirmed to me by the person in charge of the C.I.A. in Scandinavia. Original the support was given to the Abstract Expressionist and later Pop art, as a consumer art form, but most of all, a kind of cold cultural war. After all, the U.S.A. had a little culture to sell the world apart from Hollywood and music. It becomes a sell of the cold war cultural contribution by the Madison Avenue crowd, a sell of Abstract Expressionism.

The public did not know about all this before; in fact, when I told people that I believe that a massive amount of money was behind the sale of Abstract Expressionism, they told me I was wrong. It was well into the 1990s, the Independent newspaper wrote in 1995:

“For decades in art circles it was either a rumour or a joke, but now it is confirmed as a fact. The Central Intelligence Agency used American modern art – including the works of such artists as Jackson Pollock, Robert Motherwell, Willem de Kooning, and Mark Rothko – as a weapon in the Cold War. In the manner of a Renaissance prince – except that it acted secretly – the C.I.A. fostered and promoted American Abstract Expressionist painting around the world for more than 20 years. See B.B.C.

The connection is improbable. This was a period, in the 1950s and 1960s, when the great majority of Americans disliked or even despised modern art – President Truman summed up the popular view when he said: “If that’s art, then I’m a Hottentot.” As for the artists themselves, many were ex-communists barely acceptable in the America of the McCarthyite era, and certainly not the sort of people normally likely to receive U.S. government backing.

Why did the C.I.A. support them? Because in the propaganda war with the Soviet Union, this new artistic movement could be held up as proof of the creativity, intellectual freedom, and the cultural power of the U.S. Russian art, strapped into the communist ideological straitjacket, could not compete.

The existence of this policy, rumoured and disputed for many years, has now been confirmed for the first time by former C.I.A. officials. Unknown to the artists, the new American art was secretly promoted under a policy known as the “long leash” – arrangements similar in some ways to the indirect C.I.A. backing of the journal Encounter, edited by Stephen Spender.

The decision to include culture and art in the U.S. Cold War arsenal was taken as soon as the C.I.A. was founded in 1947. Dismayed at the appeal communism still had for many intellectuals and artists in the West, the new agency set up a division, the Propaganda Assets Inventory, which at its peak could influence more than 800 newspapers, magazines and public information organisations. They joked that it was like a Wurlitzer jukebox: when the C.I.A. pushed a button, it could hear whatever tune it wanted playing across the world.

The next key step came in 1950 when the International Organisations Division (IOD) was set up under Tom Braden. It was this office that subsidised the animated version of George Orwell’s Animal Farm, which sponsored American jazz artists, opera recitals, the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s international touring program. Its agents were placed in the film industry, in publishing houses, even as travel writers for the celebrated Fodor guides. And, we now know, it promoted America’s anarchic avant-garde movement, Abstract Expressionism.

B.B.C. (http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20161004-was-modern-art-a-weapon-of-the-cia) wrote a few years ago: “In the immediate aftermath of World War Two, something exciting happened in the art world in New York. Strange but irresistible energy started to crackle across the city, as artists who had struggled for years in poverty and obscurity suddenly found self-confidence and success. Together, they formed a movement that became known, in time, as Abstract Expressionism.

One of the most remarkable things about Abstract Expressionism was the speed with which it rose to international prominence. Although the artists associated with it took a long time to find their signature styles, once the movement had crystallised, by the late ’40s, it rapidly achieved first notoriety and then respect. By the ’50s, it was generally accepted that the most exciting advances in painting and sculpture were taking place in New York rather than Paris. In 1957, a year after Pollock’s death in a car crash, the Metropolitan Museum paid $30,000 for his Autumn Rhythm – an unprecedented sum of money for a painting by a contemporary artist at the time.

The following year, The New American Painting, an influential exhibition organised by New York’s Museum of Modern Art, began a year-long tour of European cities including Basel, Berlin, Brussels, Milan, Paris, and London. The triumph of Abstract Expressionism was complete.

Unwitting helpers?

Before long, though, the backlash had begun. First came Pop Art, which wrested attention away from Abstract Expressionism at the start of the ’60s. Then came the rumour-mongers, whispering that the swiftness of Abstract Expressionism’s success was somehow fishy.

It was hard going selling constructive and indeed, contemporary art in the 1960s. Although the American artist Frank Stella ultimately went to Kasmin Gallery, (that Kas had with Sheridan D ? of the Guinness family), we showed some of Frank Stella’s pictures as they represented constructive art at the time. We also showed the works of Donald Judd.

Possibly, because of my interest in architecture, I was early attracted to constructive art, with the Russian Malevich and in Holland Mondrian and De Stael. But I had very early liked works of Gustav Klimt, Marsden Hartley, and Kandinsky. I have many regrets; I specifically recall how cheap Gustav Klimt was in the early 1960s, specifically his drawings of nudes.

James Crabtree, apart from having a small architectural practice in Notting Hill, collected old Master drawings, and I recall going with him to the East End of London on Saturday mornings, collecting a truckload of master drawings, mostly student’s work from colleges, he purchased them more or less by weight and loaded on to a small truck. During the years, his collection became very valuable, and ultimately, he decided to close the gallery in 1968 and started selling at Sotheby’s small part of his collection of Master drawings for substantial money.

l can remember Robert Frazer living in Mount Street with his hipper gallery close by, and although my wife did not like me going to some of his crazy parties and events, I did a few times, there was a lot of drug-taking there; however, I never got involved, not even drinking at the time.

I had in 1965 been visiting a graphic printer in Kensington (Studio Alecto) and purchased many (possible 12-15) Hockney prints selling at the time for 20-25 Guinness each, all in relatively small editions. Later I went with James Crabtree and one of his friends to meet Hockney. I recall he was either returning or just have been in the U.S. for some time. From Hockney’s studio in Holland Park, I purchase 3 of his original works.

Alecto published Hockney’s limited edition prints in the ’60s and ’70s. Unfortunately, I brought these works later in 1968 into a partnership, and all these works become part of a business and were later sold when liquidating the business, all relatively cheap in the early 1970s.

I had already in late 1964 met John Kasmin, Hockney’s dealer, who I did not like as somehow he felt strange to me at the time. I also recall meeting Frank Lloyds at the Marlborough Gallery, who ultimately made his fortune on Mark Rothko and his death, also having Moore and Pollock at the time.

Frank Lloyds was famous for “collecting money, not art” he made his killing with the Rothko’s estate, after Mark Rothko’s suicide in early 1970, we considered that he had made hundreds of millions offshore, although involved in a lot of litigation. Most art dealers at the time were very jealous of the wealth of Frank Lloyd. (I had a large collection of gallery catalogues, including from Sidney Janis and Petty Parsons galleries. I liked Clyfford Still, Franz Kline and William de Kooning of the Abstract Expressionist)

I later did become aware of the whole business of” selling art”, specific how dealers massaged prices of artwork at auctions, moreover, how to approach curators and museums. I always had a great admiration for an artist who understood the whole business, like Anselm Kiefer in Germany and indeed Anish Kapoor and Damian Hurst in the U.K. Kiefer would make a contract with every sale where the purchaser could not sell his picture, only either back to the artist or give to public institutions, this allowed many to end up in museums and public institutions.

I have been most critical as to the marketing of art, as the world is a stage, it is all about selling yourself. The development of the artist’s estate and the huge involvement of lawyers, specific in the U.S.A., like Andy Warhol’s estate, have truly commercialised the whole scene with lawyers taking over.

In 1965/67, I was rather naive, considering it took me more than ten years to have confirmed that the C.I.A. had been spending money promoting Pop art and the American Abstract Expressionists. I have also been critical as to how auction houses have been able to “run the show” as to the medium and as an art as an investment.

In 1966, I went to my first Venice Biennale, where I recall Kasmin had several artists. I remember when Kasmin closed his gallery in the early 1970s and moved to a little office in Clifford Street. I also went to Documenta in Kassel in 1968, because of one of our artists, at the Axiom Gallery, Michael Tyzack. He was a pupil of Lucian Freud and was one of the important British artists of the modern abstract painting and took part in the IV 1968 Documenta in Kassel.

Later in 1967, I was able to buy at auction 15-20 Victorian paintings, most in attractive frames, some quite large, all purchased to fill the walls of a six-story house in Mayfair. I purchased these pictures just for decoration, not for any other interest, however, ten years later they must have been much more valuable I can’t recall paying more than £2-3000 in all for these works, purchase like old books to fill the shelves. Since I later sold the place (94 Mount Street), I can’t remember the artist, but I specifically recall a picture of Marry Queen of Scotland before her execution and some beautiful landscapes of Scotland with lakes and mountains. Victorian paintings at the time could be acquired for little money. He was the first gallery to specialise in Russian art. Mrs Gorbachev came with Margaret Thatcher to an opening, and Roy Miles did introduce very early Russian art to London.

Rental of Art (with the purchase in mind)

In 1968, I developed the idea that all the works of art standing in the various galleries, at the back or in storerooms, moreover, in artist’s studios, really needed to be seen and appreciated. In order to help to bring this art out to the public and at the same time provide an income for artists, and I developed the concept of renting the art to businesses and display in offices.

The concept of the modern office had developed in the U.K., as a result of the 60s culture. So many businesses wanted to show contemporary art, which became very much in at the time, and I believed that it was important to expose an artist work to so many eyes as possible, one could possibly encourage the sale of the work. Further, it appeared to reflect considerable modern values to show art in offices, showing an attitude towards the arts by the management.

Therefore, I wanted the art to circulate for a period, like 3-6 months in an office hanging on the wall or standing as a sculpture in reception. The company could participate, and the rental could be an operating business expense, a tax deduction. Thereafter, e.g. 3 or 5 years, the company could buy the artwork for a shilling. We would calculate the artist’s price into the rental cost.

Considering the people I involved in this, some with a very high profile, when I formed Associated Financial Planning with the Duke of St. Albans, Marquees of Reading, James Talbot and Euan Inchball. This meant I had an introduction to people, like Lord Snowden, (introduced to me by Michael, the Marquees of Reading wife, and the Dowager Marchioness of Reading, Marchioness’s daughter, Lady Jacqueline Isaacs even become a lover to Tony). All this meant that we had to take legal opinion and even speak to the Inland Revenue as to the merits and tax implications.

The Revenue, possibly because too high profile people were involved, did not allow the scheme to go ahead, since it could open the door for companies to buy expensive and valuable art, by using the annual tax deduction, eventually creating a valuable asset. I think I got a lesson, with this as it could have been a brilliant way to get art out to offices.

This ultimately meant that the scheme never went ahead. However, I later in Scandinavia, was able to get away with a somewhat similar scheme, even for quite expensive works, moreover, to have companies adopting an” in house artist” for a year and pay him out of business expenses, ultimately ending up with the artist’s work, including the decoration of factories and offices.

My Design of Logos, stationary, etc.

In 1966-68, I designed the logo for several companies in which I owned or had an investment, including lntervestor, Interfinance (Luxembourg, Geneva and New York), Intervestment Management and Associated Financial Planning (AFP). The last company’s stationery, calling cards and printed presentation, had been submitted by a major city printing firm Greenaway to the British design award (logo and stationary), which I won in 1970. The stationary had been done in three prints, raised book print, lithographic and normal book print, three types of printing.

Through the years I have designed several logos, several used today, including the Society of Technical Analysts, a highly respected society today in the City of London, I co-founded.

In 1971-74 I had an office in Duke Street St. James’s, then we had the Kaplan gallery which I also believe Kasmin was associated with. My office, in Duke Street, becomes 20 years later the White Cube gallery. I often met up with Grabowski (a Polish chemist) in 1965/66 who had a gallery and later opened at Brompton Cross, a very famous wine bar with the gallery.

One of my companies Scandinavian Mint represented Spink and Son in Scandinavia for years during the 1970s. Through the years, I came close to their coin and medal making business, also their banknote collections, further their antiques and artefacts. They issued coins on behalf of many important international organisations, including the World Wildlife Fund (W.W.F.). I started already in the late sixties to collect old banknotes; bonds share certificates. Most of this collection was also taken by the leaches of the Danish estate.

My first art collection was started in Stockholm before my son Mark was born. I had 8-9 works which I was very proud of; unfortunately, they all ended out getting lost with my near 1600 books in the London docks in 1964-65.

The second collection, in the sixties, ended up on the walls of my partnerships, ultimately being sold at auction. My third art collection started in Denmark and ultimately was taken by my estate and fiscal services. My fourth try to collect, ended sadly with everything valuable being sold and more than 300 works placed around.

During the years 1973-80, I collected many works of Miro, Chagall and many important Danish artists. I had many original works, and a large collection of Miro limited edition prints, since I knew a lady who lived next to Miro in Majorca, I arranged to have many signed personally by him. I also had many copies of Chagall’s Bible. Unfortunately, in a legal fight with the Danish fiscal authorities, I had to hand over my collection.

In the 1980s, we had a villa in Florence, located high over the city, next to Forte Belvedere. I still recall the first time I went to Forte Belvedere, the Henry Moore exhibition in 1972 at Forte Belvedere. I consider this exhibition as one of the best of his work, due to the location and the historical background of Florence.

Our address in Florence was Via San Leonardo 1; I still recall my many mornings, running early, around Florence, being surrounded by history, also our many visits to Uffizi. Those years opened up the local art scene for me, as it was impossible to live in Tuscany without valuing the past and the great history of the region. For years, I attended some great sculpture exhibitions at the Forte Belvedere, although my family and I hated having to deal with all the cars, from the many visitors, blocking our way out. I also got to know parts of the visual and performing art community.

I got to know several Italian architects such as the Alexandro brothers of Super Studio in Florence, who had won much international recognition both with their restorations, buildings and furniture. I observed the restoration of places that were planned to take more than one lifetime, giving not only the father work for 40 years plus but also his children, and they hope their children – very Italian.

When I first lived as a young man in Italy in 1959, I did not have enough wisdom to truly appreciate the Italians and their lifestyle and attitudes. However, later I gained true respect for the way the Italian lives. As now an old man, I truly appreciate the Italians attitude to life, and I hope as of writing, soon to sit in Verona or Alassio enjoying an espresso or a glass of good wine.

I have reflected on how many years I collectively have been in Italy, and it amounts to over 7 years of my life. Having lived in 9 European countries, either owned property or rented, shopping and living over relatively long periods, apart from Denmark and U.K., Italy come before Switzerland.

During my years in Tuscany, I learned how easy it would be for me to get a doctorate degree, even a professorship in the arts. My partner-in-life was considering being in charge of the Polish Cultural Centre in London, and a friend in Florence told me that she only needs a few weeks in Florence and she would get a professorship in contemporary art (Futurist), at a little price. She did not go ahead with it.

Missed on Photographs

One area I really missed out on is photography, I already in the 60s knew a photographic collector Kaspar Fleischmann, founder of the Galerie Zur Stockeregg in Zurich, he established the photography sector of Art Basel and co-founded the AIPAD Show New York and Paris Photo. And I had started collecting old pictures of Copenhagen from the 19″’ Century; however, I never took advantage of all this. At the time, one could count on one hand, the number of galleries specialising in photographic art. Only in the U.S.A., New York, and L.A., one could find an interest in this art form. I ignored it, because, I considered it was too easy to duplicate, and photographs would cause ultimate despair. Seeing today the hundreds of galleries, in fact, thousands around the world, the many exhibitions, it has really developed to big business.

A&A

In London, l joined the Art & Architecture society in mid-1980, where many famous artists mixed with architects, our objective was to bring the arts more into architecture, which had become dominated by engineers, since the Italian engineer Nervi. As a Dane, I had been used to see architects using artists very early as to their interiors. During these years, I got to know many of the leading British architects, including lesser-known like Theo Crosby, Nicholas Grimshaw, and artists like Caro. To me, visual art is most important in architecture. In fact, I used to say that Scandinavian architects built a house from the inside out, whereas South Americans build them as large outside sculptures in nature. It is interesting to see the ultimate beautiful sculptures of buildings by architects like Zaha Hadid and Frank Gerry.

Having already back in 1966 been involved with contemporary art with Axiom Gallery, I decided in 1985 to form Axiom Art Associates, A.A.A. with the objective to expand access to contemporary art and support local artist communities. We sold limited edition, signed and framed prints, delivered with a certificate of authenticity. We wanted to invite first-time buyers and collectors to buy art; unfortunately, at the time the Internet did not exist; however, later, this concept was very successfully adapted to the Internet by several companies.

During my time as chair of The Mayfair Society and The Mayfair Trust, I was a patron of the Royal Academy of Arts attending for eight years most shows and events; I also knew many of the leading people in the visual arts and gallery owners in Mayfair, including the Waddington, Angela Juda and the Gimpel Fils. In the early 1990s, I tried to involve some of these people in the plans for an exhibition in Hyde Park with large marques space like the FIAC in Paris. Such an exhibition should include Modern Master, but mostly show contemporary works selected by British galleries and dealers from around the world. I wanted the event to follow the annual Grosvenor Antique Fair, which had already introduced modern masters. The Royal Parks was very difficult at the time, and they just dragged their feet’s and sadly nothing become of it, however, 10-12 years later they did allow the Frieze into Regent Park.

During the 1980s and 90s, I regularly went to the Venice Biennale, Dokumenta in Kassel; and attended the FIAC and Basel Art Fairs. It was, as mentioned before, difficult to “sell” contemporary art in the U.K. in the 1980s and early 1990s.

One of my sons lived in Berlin in the early 1990s; I did propose a project, which I did not continue with, to restore an old building at Unter Den Linden (a central street), where the concept was for visual art to be mixed with a bookshop, Café and restaurants, even with sales of fresh flowers and food. I look with considerable admiration on seeing Berlin re-taking its role, as a capital with a large art scene.

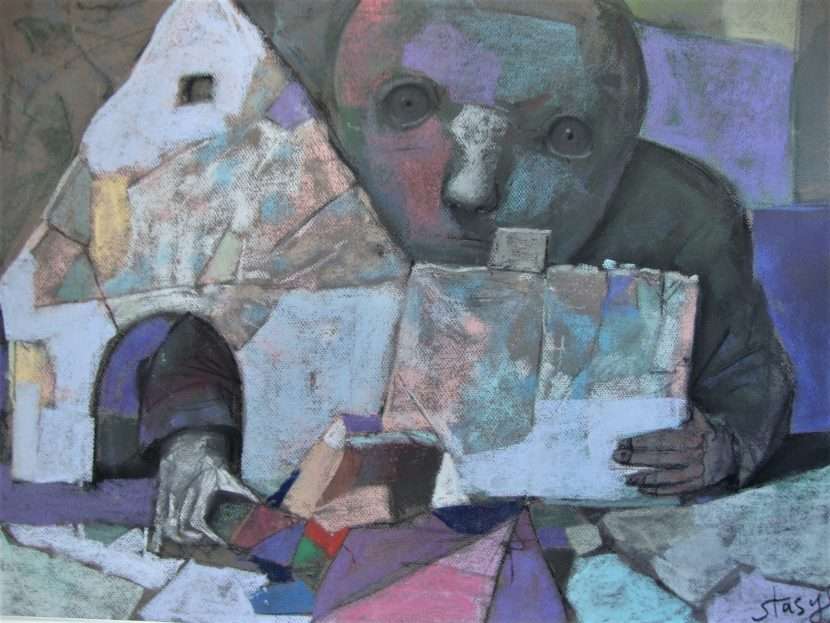

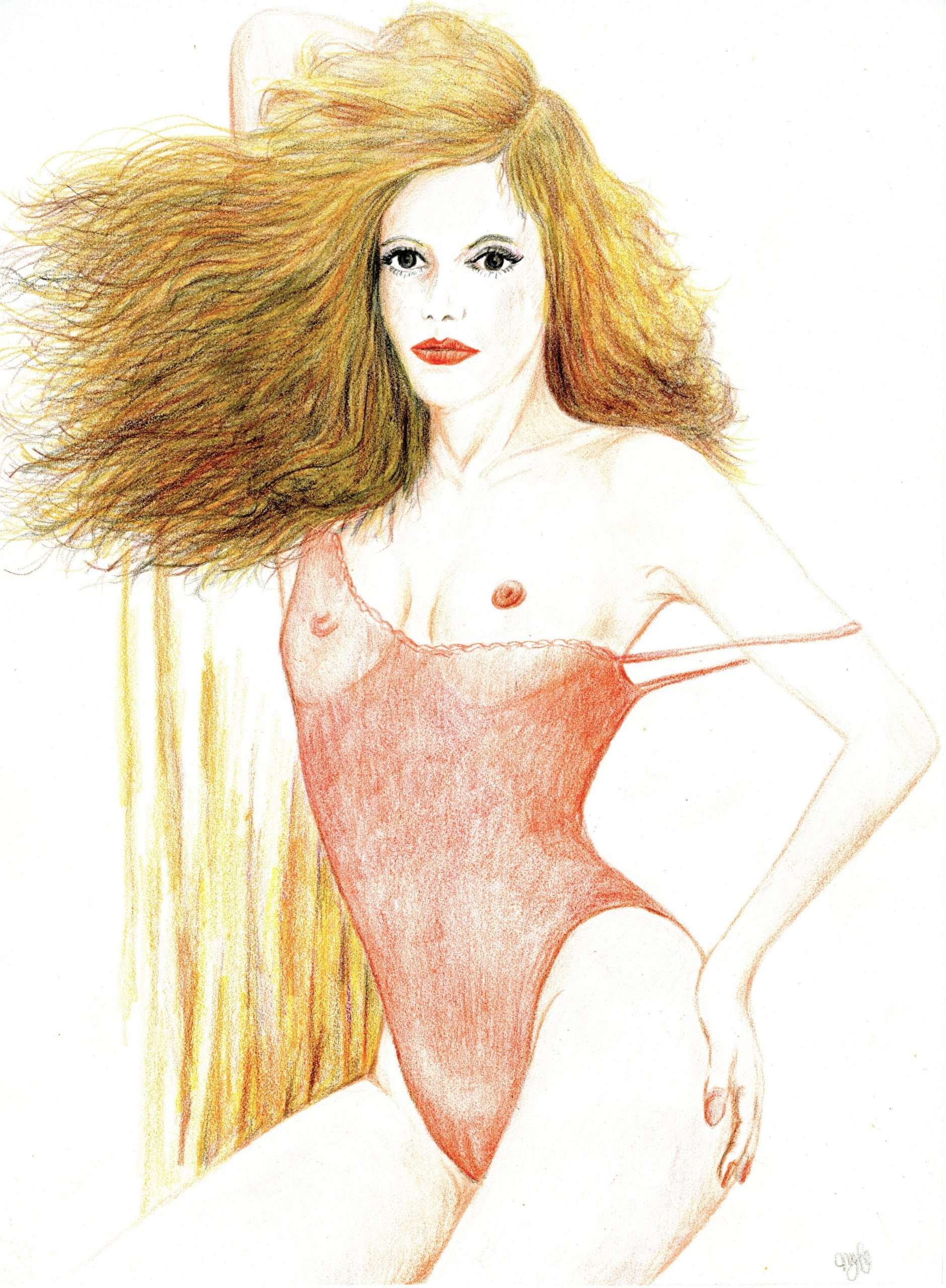

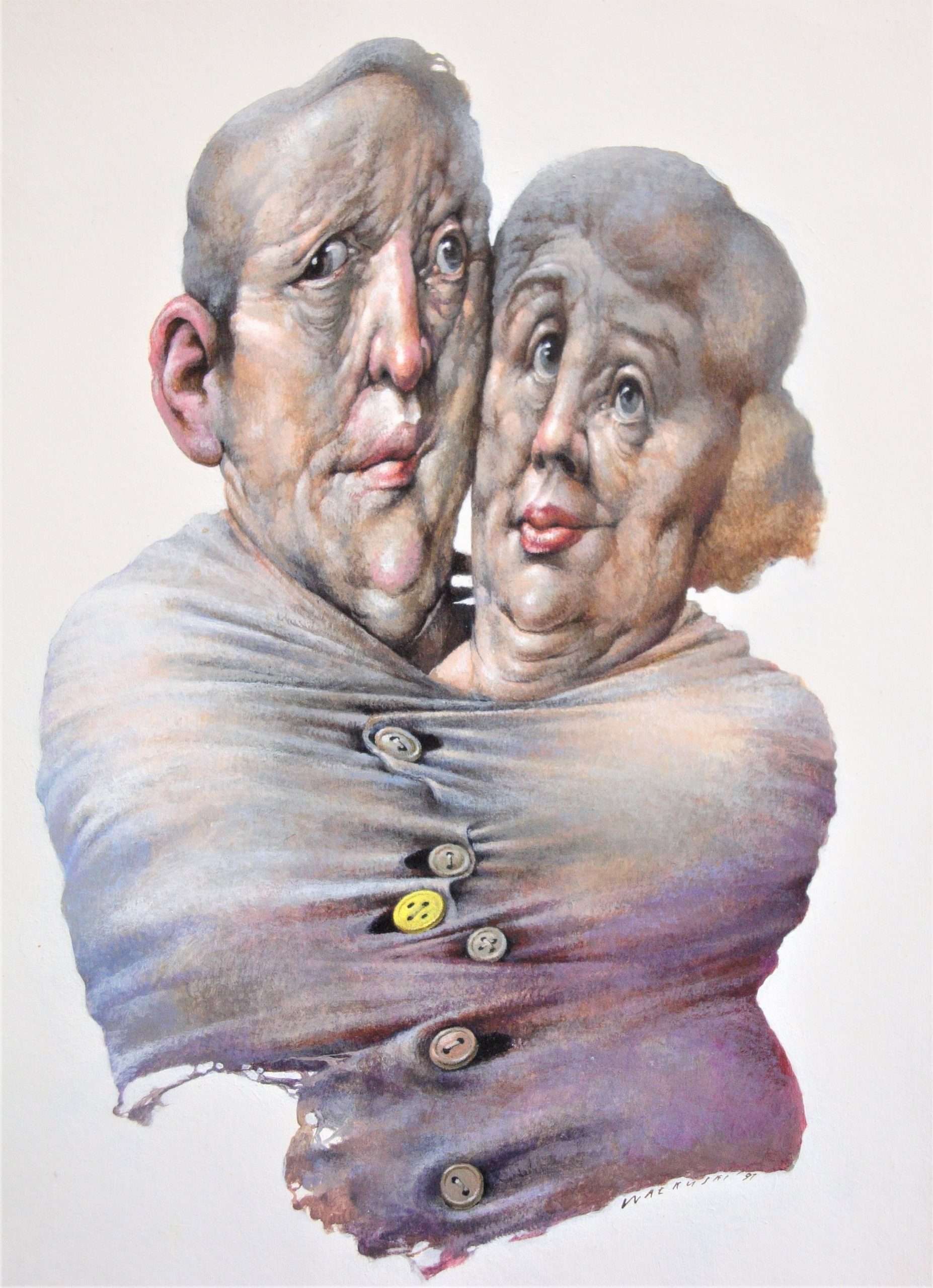

Making regular annual visits to Poland, I learned about the local art scene in Warsaw and Cracow and started collecting a large number of works by Polish artists, including Stasys and Walkuski. I become an adviser to them and other artists, as my soul mate and partner-in-life took a few promising classical musicians under her belt, including a pianist original found by Leonard Bernstein, Marek Drewnowski.

Roy Miles

In the mid-1980s I got to know Roy Miles privately, only he was a very private person in many respect. And I did not know much about his past except that he had been a hairdresser and had a reputation of re-inventing the interest in Victorian painters.

As one of his obituaries goes: “Once upon a time, before celebrity cooks, celebrity gardeners and celebrity interior decorators, there was a celebrity art dealer Roy Miles” That is so true, Roy knew how to sell art, and he had been a pioneer of Victorian paintings from the early 1970s when no one was interested, and the market was dominated by low pieces.

According to his obituary in The Times: In 1971 he opened his first “gallery”, in a flat in Eaton Place. To begin with, he specialised in 18th- and 19th-century sporting pictures, including works by Stubbs and Munnings, later concentrating on Victorian paintings.

From his early days in London, Miles showed a flair for befriending the rich and famous. Early acquaintances included the government minister Alan Lennox-Boyd and his wife Patricia, and the Beatles’ manager Brian Epstein. At a beach party in Italy he met Farouk, the “charming” exiled King of Egypt, while in the South of France he was invited to dinner with the Aga Khan.

To me, Roy really had met more famous people than mentioned in his obituary. To some of Miles’s acquaintances, the biggest surprise in his memoirs was the appearance of his wife Christine, née Rhodes, a member of the Yorkshire “county set” whom he had married in 1970.

By this time, the fine art market had taken a downturn, and Miles was struggling financially. In 1998 he closed his gallery, though he continued to work as a consultant. But he had no regrets, observing in his memoirs: “I entertained the great and the good, travelled the world, met rich and famous people, was part of a once-great market and reached the top of the tree.”

I later brought Roy Miles to 27 Berkeley Square with his ground-breaking contemporary Russian shows of the late Eighties, another celebrated but short-lived innovation typical of the dizzy peaks and conversely deep troughs that characterised his career.

He was the first gallery to specialise in Russian art. Mrs Gorbachev came with Margaret Thatcher to an opening, and Roy Miles did introduce very early Russian art to London.

Roy Miles was the first and perhaps the last of these, possessing the personality, presence and drive to add a whole new dimension to the art of shifting canvas. To me, he was certainly a good example of how art needs to be sold.

Through the years I have followed Larry Gagosian, one of the greatest salesmen of art in the last forty years plus whom I have considerable respect for. However, others argue that the big gallery system hypes artists of questionable talent to meet bottomless demand for high-priced art. The critic Jerry Saltz wrote this assessment: “Something happens to people when they sign with the megas. Too often, the artists are brought in at mid-career, and – like 34-year-olds signed by the Yankees – they are poised for a decline. Every show of living artists in these galleries is ushered in like a career retrospective, a quasi-coronation, with everything often already sold or spoken for. There’s no space for debate about the merits. Many of these shows are too big by half, filled with dross. The artist is a brand, and the brand supersedes the art.” Anybody who wants to be an art dealer and be any good – it takes a lot of time, a lot of work.” as Gagosian’s told the FT recently. Competition, success, hard work, energy, opportunity, motion. I agree, as with everything and in businesses..

The Mayfair Society was first established back in the late 1920’s by a group of high-society members of Mayfair, to enhance the social and charitable aspects of Mayfair, London. Although, the society did continue its good work right up to the Second World War, due to world events more serious matters took over. In 1988, the Society was relaunched by prominent members of the Mayfair establishment and the Mayfair Residents Association (RAM).

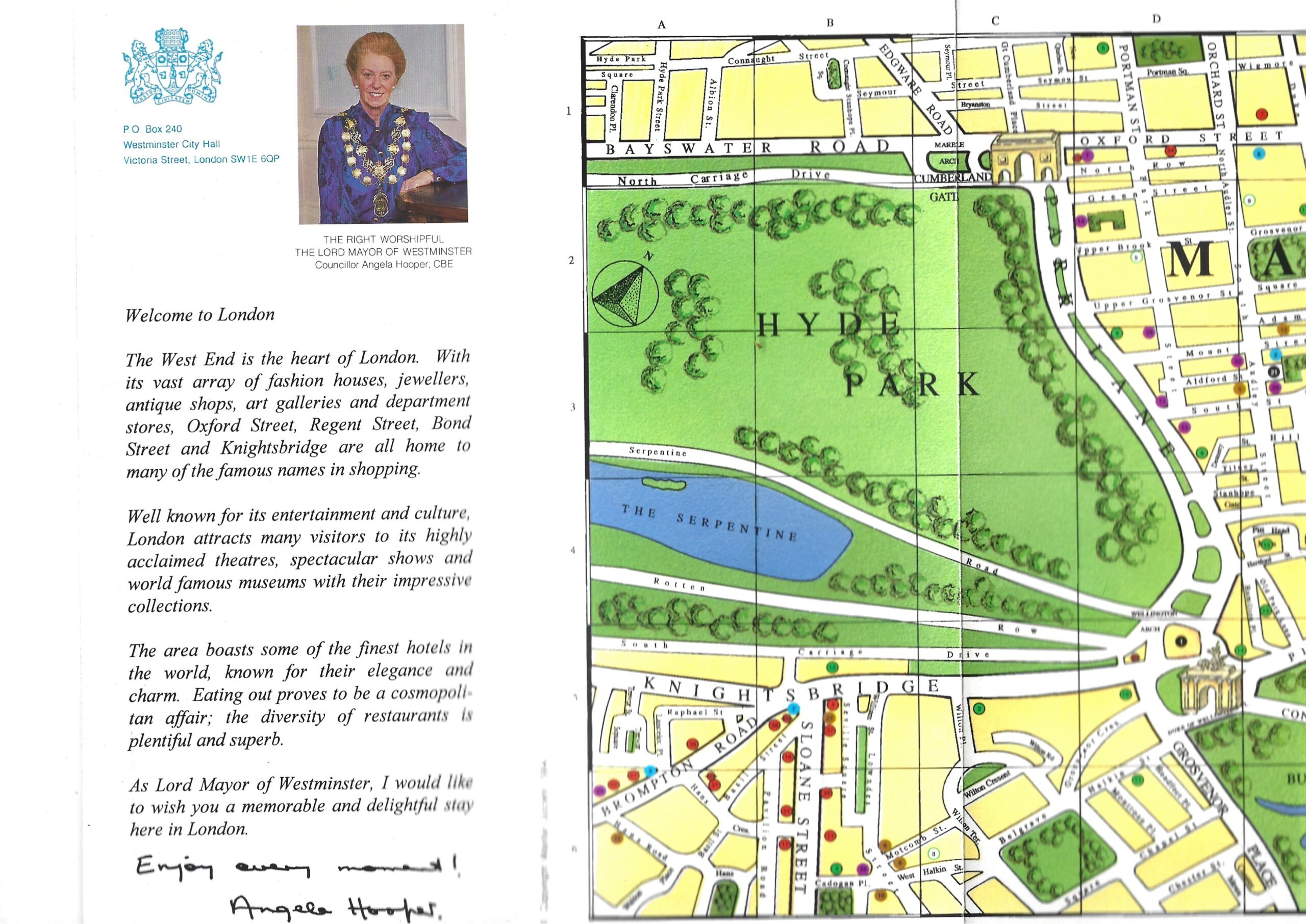

Mayfair is a unique area and one of the most famous shopping areas in the world with some of the most exclusive antiques, jewellers and fashion shops. Famous shopping streets include Old and New Bond Street, Piccadilly, Regent Street, Savile Row, South Molton Street, Burlington’s and Royal Arcade and a major part of Oxford Street.

The name Mayfair has depicted high standards, distinguish, luxurious, abundant, affluent, grandeur’s, well-to-do, richness, elegant, prosperity and quality. Therefore, the name is used all over the world for major products and services, including cigarettes, liquor, cars and hotels to name a few.

Although the name was important, no doubt it was the location which attracted some of the largest property companies to Mayfair. After all, they should know about the location. Mayfair also houses several multinational companies and numerous other major businesses including some of the best retailers in the land and the world.

Mayfair provides the few landlords in the area with the highest rental and capital values in the world. Considerable purchases of large residential properties by foreign rulers and nobility clearly state the area’s attractiveness.

Mayfair also includes more than twenty-five major hotels, ranging from Claridge’s to the Grosvenor House at Park Lane, The Dorchester to The Lanesborough at the border of Mayfair at Hyde Park Corner to Ritz (also on the border of Mayfair), nearly 300 restaurants, clubs, casinos and public houses, 100 travel agents and 75 airlines offices. Moreover, the arts are presented with more than 125 art galleries, the Royal Academy of Art, 100 antique shops and 50 interior design businesses with several auction houses including the largest in the world Sotheby’s. Mayfair also contains businesses such as the largest Rolls Royce dealer and many luxury car salesrooms.

Into the Mayfair, melting pot goes also more than 40 embassies and foreign delegations including the American, Japanese, Saudi Ara¬bian and Italian Embassy. Many multinationals have their headquarters in Mayfair, including such giants as the world’s largest advertising agency and GlaxoWellcome, the largest pharmaceutical company in Europe.

Mayfair and the Arts

London has long been considered to be one of the world’s greatest artistic centres, particularly for Fine Arts, both on a cultural and a commercial level. London’s commercial art market, which has become focused increasingly around Mayfair over the past 200 years and has a long and interesting history including the Royal Academy of Art, The London Institute, numerous Galleries, Auction Houses, buildings of high architectural quality, environment and interior as well as many art collectors who have lived in the Mayfair area. A number of Mayfair’s galleries date back to the 18th century, when it started to become a fashionable residential area and when the London art market established itself. This ‘establishment’ was marked by the foundation of four top fine art auctioneers: Sotheby’s 1744; Christie’s 1766; Bonham’s 1793; and Phillips 1796. Today, there are more than 100 commercial art galleries in Mayfair with a further 800 spread over the greater London area. The volume of their transactions is amazing – for example, in one year Sotheby’s alone handled ten times more sales than were recorded in the whole of France for that same year.

The London Institute is the largest institute of art in the world. The Royal Academy of Art in Piccadilly, Mayfair, is the oldest society in England devoted to Fine Art since it was founded in 1768. Names such as Bond Street, Bruton Street, Davies Street, Albemarle Street and Cork Street have become synonymous with the best art in the world. What specifically makes Mayfair attractive is its ambience, augmented by more than 200 restaurants and 25 major hotels.

As one of the most fascinating areas in Central London, Mayfair boasts magnificent buildings, dating from the early 17th Century. The best British hotels, combined with superb architecture and the Bohemian spirit of the area, create a unique charm. These attractions have, in the past, enticed a large cross-section of the commercial market to the area. Businesses are encouraged to establish themselves in Mayfair by the delightful surroundings and the prestigious location, as well as the vibrantly diverse artistic and commercial backdrop.

Fountains and Permanent Sculptures

I wrote in 1988 the above about The Mayfair Society and about Mayfair and London that it has long been considered to be one of the world’s greatest artistic centres particularly for Fine Arts, both on a cultural and a commercial level. London’s commercial art market, which has become focused increasingly around Mayfair over the past 200 years and has a long and interesting history including the Royal Academy of Art, The London Institute, numerous Galleries, Auction Houses, buildings of high architectural quality, environment and interior as well as many art collectors who have lived in the Mayfair area.

The Art for Mayfair and The Mayfair Society held nearly two hundred exhibitions, nearly all overseen to and curated by me, some with the assistance of respected curators and scholars. Just to mention a few of these exhibitions in the various galleries in Mayfair:

The official launch of the Art for Mayfair in 1990 was in the presence of the two former ministers of the Arts, Lord Gowrie and Lord St. John of Fawsley and the then present Minister of the Arts, the Right, Hon. Peter Brook, CH, MP,

- The Art for Mayfair Christmas Exhibition. Opened in the presence of H.R.H. Princess Margaret.

- 3 Colourful Friends The exhibition was opened by His Excellency the Brazilian Ambassador and his wife

- The Window into the South African Landscape. Nigel Mullins, opened by Chief Anyaoku, the Commonwealth Secretary-General, in honour of South Africa having rejoined the Commonwealth.

- The Royal College of Art’s Scholarship for Menswear Tailoring. This annual competition was held by the Art for Mayfair and judged by Lord Lindley, senior members of the fashion world and The Royal College of Art. This annual event is sponsored by Dunhill.

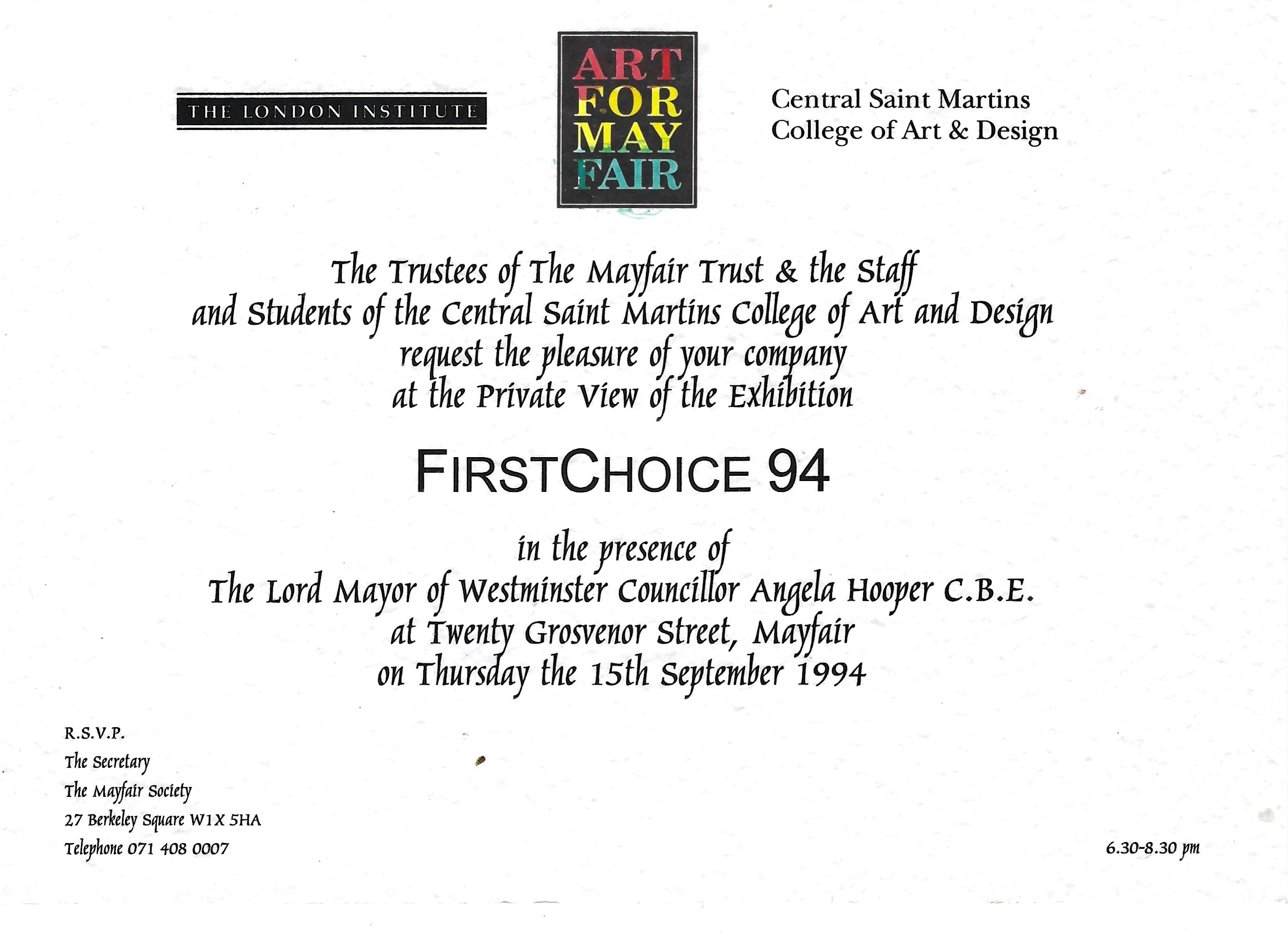

- FirstChoice. In collaboration with The London Institute and Central St Martin’s College of Art and Design. Opened by the Lord Mayor of Westminster Councillor Angela Hooper, C.B.E. and Baroness Hooper.

- Jess Downs. The private view was opened by Darcey Bussell, the prima ballerina of The Royal Ballet.

- Zimbabwe96. Chosen in connection with the Africa96 exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts. Opened by the Commonwealth Secretary-General, Chief Anayouku.

- MultiMedia2. Multimedia exhibition at Lansdowne House with Brian Eno, Peter Greenaway (world premiere of the new film), Tom Phillips RA, Bruce McLean, Sachiko Odashima and Colin Self.

- Nicole Ryan & Wendy Meaden. Wendy Meaden’s exhibition formed part of the TAIS (Temporary Art Installation Scheme), devised by The Mayfair Society and held at One Mount Street Gallery.

- Bruce McLean. This print exhibition by Bruce McLean, a major figure in the contemporary art world, featured a collection of his limited edition prints held at 22 Grosvenor Street Gallery.

- Artis Bute. Already popular in Latvia, Art for Mayfair sponsored Bute’s first exhibition in London. The occasion was opened by the Minister of Foreign Affairs for Latvia together with the ambassadors from Estonia and Latvia. The President of Latvia sent a special greeting, extending his very best wishes to The Mayfair Society and to an artist who is held in high esteem by his countrymen.

- Heidi Sauter. Heidi Sauter work was previously featured as part of a mixed private view’ Abstract Art is Beautiful’, back in November 1994. However, since then, Sauter has produced several more series of large and beautiful works, including the Buddha’s Dance and Black Water Light series.

- James Elliott. One Davies Street became the focal point of great interest on the evening of the exhibition, “Sex, Money and Summer Madness”. James Elliott, the photographer, made a grand entrance, into the exhibition, via a Cadillac, balancing on each arm the subjects of his extraordinary photography – Selena and Tracey, the two glamour models featured in a large selection of his works. In addition to the gallery event, a special Happening took place in Berkeley Square.

- Zimbabwe95. Zimbabwe95 celebrated the work of five Zimbabwean artists. This was an excellent opportunity for these five African artists to make their work known in London, as the capital was being extensively introduced to African art from the whole continent, especially via the Africa95 exhibition, opened by the Queen.

- Helen Lieros. Originally of Greek parentage, born in Zimbabwe and educated in Europe, Lieros combines her European and African influences, portraying the feelings that she has for her Greek roots and culture. A successful exhibition took place in Davies Street Gallery.

We had a long list of other exhibitions, including; ArtLand – Look@Me – London&MyArt – ARTspace, London2020, Art4Mayfair, Art4London, ART horizons, 21stCentury A R T and BLUESpace4U – MayfairPortraits

The CityScape

Back in the mid-1980s, I found that the streets scapes were blackened by empty shops, the famous street in the West-end of London had many retail premises which remain empty, dirty and dilapidated for a long time, bringing the whole image and general standing of an area down. Moreover, this was somewhat, unfair for shops paying their way and attracting customers and tourists to London. At the time Lord Fawsley chaired the Royal Fine Art Commission and lived in Mayfair. I spoke many times to him as to my ideas on how to impose standards on builders and indeed on planning, further, to protect more and not to harm the local community when builders moved into the area. I wanted builders and owners to share in the maintenance of a community spirit.

Pedestrianise Oxford, Regent and Bond Street

Although, only in rough layout in 1989, my plans to pedestrianise Oxford Street and Regent Street (with electric tramps) and pedestrianise Bond Street and most part of Mayfair including to bring the car traffic under Park Lane and Piccadilly under the road, did not go down well.

Despite this would take away a large amount of pollution and noise, moreover, allowing people to walk into Hyde Park and St-James’s Park. I discussed the rough proposal with the Royal Fine Art Commission, where Richard Rogers made a loose assessment of the costs in the late 1980s.

Having seen and experiences that they had done in Paris, I believed that bringing Park Land and Piccadilly under the road so to say, would better the environment and indeed the value of the properties around. I see that 30 years later, in 2020, Oxford Street should be pedestrianised, but I also see that buses are still lining up the street with diesel pollution.

I wanted local governments in the U.K. not to allow shops on the main street the remain empty; there should be an obligation by the landlords to regular paint and keep the shop windows clean and even allow goods to be displayed in the shop windows. Charities and other non-profit institutions had a preference to use empty shops. Considering that at the time in the U.K., Business rates still had to be paid by the landlord, although reduced, when the premises were empty, I proposed that by offering charities temporary occupation, accepting their registered credential and aims, the landlords could “share” the reduced rates levied on registered charities use of the premises, as to Business rates.

Although there was the usual opposition to such proposals, several landlords accepted to try out this and signed agreements with popular charities. Since the West End of London commands the highest property values in the land, therefore attracting considerable Business rates, a shop in a prime location was expensive for the landlord to keep empty. Apart from retail premises, I could see no reason why empty office buildings and premises could not be subject to the same concept, by sharing their Business rates with the landlords when occupied by registered charities.

At the time, I was the chair for the local amenity groups in Mayfair, appointed by Westminster City Council (W.C.C.). The Ward of Mayfair included Soho. It was our responsibility to deal with the local planning application, together with the Westminster Council (one year more than 1600) and discuss with the local community, changes of use, extensions, new building projects, etc. Despite this, I wrote about my ideas and concept, and indeed set out everything in our magazine ” Inside Mayfair “, the important landlords and landowners were reluctant to enter into the scheme with charity occupation. They knew I had been advocating for years that property owners and developers should contribute some percentage of building cost to the arts.

Enforce a Code of Conduct on Builders

Builders at the time seemed to be a hit and run affair; many left the place without any consideration for their surroundings. I suggested to W.C.C to enforce a code of conduct on builders with quality standards etc. including decorating their hoardings, work within certain hours, etc. in general to reduce the impact on the local community. This ultimately leads to the Builders Better Scheme, launched by Westminster City Council in the late 1980s.

At the time builders could leave building sites looking like a bomb site and dirty, moreover disturb the neighbours with work out of hours. I tried to involve the Art colleges, as to the decorations of the hoardings, but I found that many students were rather spoiled, and demanded too much to contribute to hoardings artwork. This later meant that most property companies showed a picture of the finished buildings instead.

One percentage – for the arts

Westminster City Council was considered the most important council as to money, encumbering the most valuable properties in London, including West-End, Mayfair, St. James’s, Belgravia Pimlico and Westminster. I had from my first days been working with the planning department of W.W.C. and tried to advocate the adoption of the 1% for the arts from developers building costs, like for years in the U.S.A. In addition, I advocated for developers to provide ” planning gains for the local community” in return for planning permission. This was very difficult at the time, as property developers, did so many hits and run buildings around, totally ignoring the local community. Moreover, I found that both the large landowners and property companies had corrupted major councils by having their own people either in their planning department or as councillors.

The largest British property company at the time would go so far as to pay for the education of people and look after them for 10-15 years before using them. Planning has and still is the place where the political parties are able to “pay” their supporters and members. Just a change of use can make millions, mostly without the taxpayers’ knowledge and loss.

I fought actively for years to protect residential use in Mayfair and indeed led our association to go to court, including to the House of Lords, against the major landowners wish to extend the so-called temporary office licenses issued after the Second World War. At the time commercial properties in the area were valued up to 7 times more than residential.

My actions at the time did create very powerful enemies, but I was right in the end. Residential properties today are valued much higher than commercial space. Being very early a member of the Art & Architecture society, which advocated the integration of the arts in architecture, it was natural for me to suggest that London should have an annual or biannual art festival, starting with the West-End of London.

Alone in Mayfair, we had hundreds of art galleries, The Royal Academy of Art was located in Mayfair at Piccadilly. I named the project idea Art for London and Art for Mayfair. Moreover, we had Sotheby and Phillips auction houses, with Christie’s close by in St. James’s (part of the Ward). By bringing art into the concept of charity shops, I suggested that students from the various art colleges could be allowed to display their works.

When I heard in the late 1980s that the London Institute was looking for a new place for their main office, I suggested for them to temporarily move into Mayfair, at the back of Bond Street Station, a Grosvenor Estate property. Due to an overall new development plan, which could not go ahead for years, therefore, offering London Institute a relatively cheap solution for some years. London Institute was at the time the largest art education institution in the world with 20,000 students, including Central School St. Martins, Printers College and London Fashion, Camberwell, Chelsea and several more colleges.

This all provided a unique opportunity to combine my concept for Art for London and Mayfair, with graduates work coming from various colleges. So in 1990, I finally launch the Art for Mayfair with The Mayfair Society, attended by the then Minister of Arts, and two former ministers of Arts (Peter Brooke, Lord Fawsley and Lord Gowrie).

The launch took place in 60 Brook Street, a building opposite Claridges Hotel (who provided the catering). The building had previously been occupied by the respected art dealers Bloomé and Alistair McAlpine. I had succeeded in activating The Mayfair Society from the 1930s and also The Mayfair Trust (both of which I chaired for years) to sponsor the scheme, in addition to prominent local property companies (Grosvenor Estate and Chelsfields). Through the years, we have had close to 200 exhibitions in prominent gallery locations in Mayfair (Grosvenor, Brook, Park and Davies Street). We held the best of the graduate show of graduates from the Central School of St. Martins and other colleges.

All these events were opened by prominent people, ranging from royalty (Prince Charles, Princess Margaret) to ambassadors (we have 31 embassies in Mayfair) and members of the government. We were the first to introduce fashion shows and product promotions into unusual places, including in art galleries.

We had graduating shows of several famous designers from St. Martins including Husain, Galiano and Alexander (Lee) McQueen, many sponsored by local retail companies. When the Queen opened the Art of Africa, we held a series of the exhibition including West-African Art, A Window to South Africa, Zimbabwe, all coordinated with Chief Emeka Anyaoka, the Commonwealth Secretary-General for many years, and a Mayfair resident. In some exhibitions, we included decorative objects, such as glass, ceramic and other craftworks. The Mayfair Society together with Axiom Art Associates advised several large companies in Mayfair, to have a corporate art program, building up an in-house art collection and indeed support young artists and art events (companies such as I.C.I., Zeneca and Smith Kline Beecham).

I advocated for years that commercial art galleries and artists should be allowed to exhibit large sculptures in green spaces like Berkeley, Hannover and Grosvenor Square. Further, to exhibit sculptures on large pavement and sidewalks. I worked for many years to raise money, through my chair of The Mayfair Trust, for the protection and restoration of the property in Brook Street where Frederick Handel had live for many years, in addition, to where William Blake had been living in South Moulton Street. Even the apartment that Jimi Hendrix had stayed in next door to Handel in Brook Street, we tried to involve the lottery people, although it was the early days in the early 1990s. I know that Handel’s house and Jimi Hendrix’s apartment has now been restored and protected.

ART FOR LONDON – ART FOR MAYFAIR

I suggested in 1988 to create an annual event around the Arts in London (Art for London) likewise an event for Mayfair (Art for Mayfair). As to Art for Mayfair, the event I wanted was to hold an annual Art week or month together with the many commercial galleries in Mayfair, possible with the involvement of the Royal Academy of Art, a Mayfair institution and possibly some of the auction houses. At the time, we had close to one hundred galleries in Mayfair and St.James’s. It was an uphill struggle – I did spend a large amount of time and energy to achieve just something; but very difficult at the time and in the end I walked away as I did from Mayfair and London.

At least in 2013, after nearly 20 years, the first Mayfair Art Week was held, and even with the many commercial galleries included, even that it took 20 years, at least something came about.

Art in Hyde Park

For a number of years, I worked hard to create the foundation to hold a large contemporary art exhibition in Hyde Park. The Royal Parks was at the time very difficult to get to do anything in the parks. For many years they had only allowed the Japanese ones and then the Pavarotti which Princess Diana had something to do with.

I wanted to take advantage of the newly designed large tents, which they used successfully in Paris when the FIAC had to move out of the Grand Palais. It was difficult to convince the Royal Parks at the time, with the old guard still in charge, however, ten years later they agreed to hold the Frieze in Regent’s Park. The Frieze becomes very successful.

Opera

I was first introduced to Opera, if that is the right word, at the “tender” age of 16, by my business partner Edgar Midling-Jensen, who after the war had studied for many years as an opera singer in Rome and had hoped to become a performing singer. He was well-known in Norway as he was a famous freedom fighter who escaped the German capture so many times.

When Edgar and I in 1957-58 were travelling in Norway and Sweden, visiting shipowners, in his large American car, driving sometimes for many hours, he sang all the various arias, the long song accompanying a solo voice.

He taught me to listen to these huge arias, from Don Giovanni, Turandot, to Carmen, Habenera to Samson and Dalila. I still recall him singing Figaro’s role “Non pui andrai” from Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro and the “Bella Siccome Un Angelo” Aria from “Don Pasquale” and “Der Vogelfanger bin ich ja” from Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte sung by Papageno, this famous aria wanting where he wants to find a wife or a least a girlfriend, as he is an old man, just like me now.

It was from this experience as a background, that got me to show my cultural upbringing and to book three tickets to Teatro alla Scale in 1959, as I was living in Portofino. I was only 18 years old and wanted to appear cultured and refined for the Italian, as I was dating a daughter of an old banking house in Genova.

La Scala had La Boheme on its calendar, and I felt I looked cultured to my possible future in-laws if I took their daughter to Opera. So, at great expense, I organised three tickets, even in a loge, the front section of the lowest balcony.

Why three, first my “girlfriend” Alessia, her chaperone and myself. Yes, we had to travel to Milan, for hours, with her chaperone, even in La Scale, I was unable to sit next to my girlfriend. The “ugly” chaperone insisted on seating between us, and she slept in the same hotel room as my girlfriend, so little chance to do anything. Anyway, my girlfriend Alessia hated the Opera and much rather listen to Bobby Darin “Dream Lover” or Connie Francis, the American singer singing Italian” Comm’e Bella a Stagione” and “Ciao Ciao Bambino”. I purchased Connie Francis album in 1959 of Italian songs and gave Alessia as a birthday present.